Celebrate Poe

Celebrate Poe

A Real Railway?

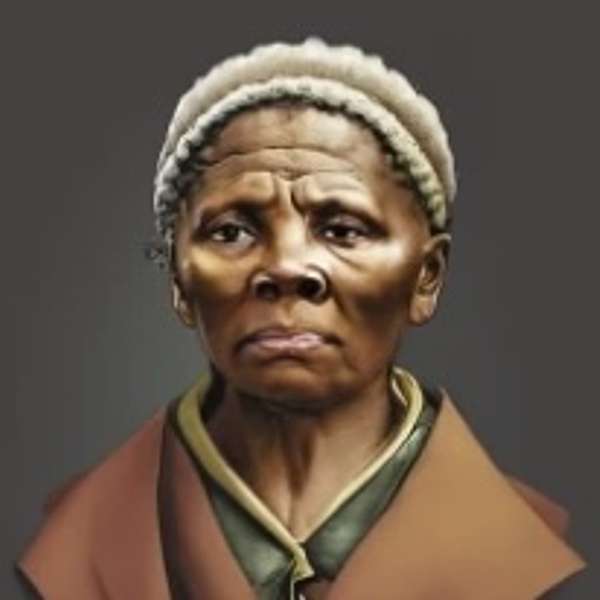

Episode 222 is the second of a three part series dealing with Harriet Tubman, and her work with the Underground Railway.

The episode deals with some of the brave efforts towards liberation that Tubman led, and ends with this description of the assault on Fort Wagner: And then we saw the lightning, and that was the guns; and then we heard the thunder, and that was the big guns; and then we heard the rain falling, and that was the drops of blood falling; and when we came to get the crops, it was dead men that we reaped.

Thank you for experiencing Celebrate Poe.

Welcome to Celebrate Poe - Episode 222 - A Real Railway?

This is the second of a three part series about Harriet Tubman.

Now I have a confession to make - I had finished all three episodes dealing with Harriet Tubman, became waylaid, ended up doing some other things, and forgot completely about the final two Tubman episodes - and since today is the last day of Black History month, I will release part two dealing with Tubman, and then immediately release part three.

I’d like to start the main portion of this episode with a quote by Hopkins Bradford in her classic Harriet: The Moses of Her People regarding Harriet Tubman.

It would be impossible here to give a detailed account of the journeys and labors of this intrepid woman for the redemption of her kindred and friends, during the years that followed. Those years were spent in work, almost by night and day, with the one object of the rescue of her people from slavery. All her wages were laid away with this sole purpose, and as soon as a sufficient amount was secured, she disappeared from her Northern home, and as suddenly and mysteriously she appeared some dark night at the door of one of the cabins on a plantation, where a trembling band of fugitives, forewarned as to time and place, were anxiously awaiting their deliverer. Then she piloted them North, traveling by night, hiding by day, scaling the mountains, fording the rivers, threading the forests, lying concealed as the pursuers passed them. She, carrying the babies, drugged with paregoric, in a basket on her arm. So she went nineteen times, and so she brought away over three hundred pieces of living and breathing " property," with God given souls.

Now after reaching Philadelphia, Harriett thought of her family. "I was a stranger in a strange land,”" My father, my mother, my brothers, and sisters, and friends were [in Maryland]. But I was free, and they should be free.”

In December 1850, Tubman was warned that her niece Kessiah and Kessiah's children would soon be sold in Cambridge. Tubman went to Baltimore, where her brother-in-law Tom Tubman hid her until the sale. Kessiah's husband, a free black man named John Bowley, made the winning bid for his wife. While the auctioneer stepped away to have lunch, John, Kessiah and their children escaped to a nearby safe house. When night fell, Bowley sailed the family on a log canoe 60 miles to Baltimore, where they met with Tubman, who brought the family to Philadelphia.

Early next year Tubman returned to Maryland to guide away other family members. During her second trip, she recovered her youngest brother, Moses, along with two other men. Word of her exploits had encouraged her family, and she became more confident with each trip to Maryland.

In late 1851, Tubman returned to Dorchester County for the first time since her escape, this time to find her husband John. When she arrived there, she learned that John had married another woman named Caroline. Tubman sent word that he should join her, but he insisted that he was happy where he was. Suppressing her anger, she found some enslaved people who wanted to escape and led them to Philadelphia.

For the next 10 years, Tubman returned repeatedly to the Eastern Shore of Maryland, rescuing some 70 slaves in about 13 expeditions, including her other brothers, Henry, Ben, and Robert, their wives and some of their children. She also provided specific instructions to 50 to 60 additional enslaved people who escaped. This was when she first got the nickname “Moses” alluding to the biblical prophet who led the Hebrews to freedom from Egypt.

Now before I go any further - I better address a common question - was the Underground Railroad a real railway. No, it was not a railway in the sense of steams, rails, and trains, but Tubman’s dangerous work required ingenuity. She usually worked during winter, when long nights and cold weather minimized the chance of being seen. She would start the escapes on Saturday evenings, since newspapers would not print runaway notices until Monday morning. So, in answer to the question was The Underground Railway a railway - well, actually it was more of a network leading to freedom.

Harriet Tubman had no problems using subterfuge to avoid detection. Tubman once disguised herself with a bonnet and carried two live chickens to give the appearance of running . Suddenly finding herself walking toward a former enslaver, she yanked the strings holding the birds' legs, and their agitation allowed her to avoid eye contact. Later she recognized a fellow train passenger as a former enslaver; she snatched a nearby newspaper and pretended to read. Tubman was widely known to be illiterate, so the man ignored her.

Tubman's faith continued to be an important resource as she ventured repeatedly into Maryland. The visions from her childhood head injury continued, and she saw them as divine premonitions. She spoke of "consulting with God", and trusted that He would keep her safe. Quaker Garrett once said of her, "I never met with any person of any color who had more confidence in the voice of God, as spoken direct to her soul."Her faith also provided immediate assistance. She used spirituals as coded messages, warning fellow travelers of danger or to signal a clear path. She sang versions of "Go Down Moses" and changed the lyrics to indicate that it was either safe or too dangerous to proceed. As she led escapees across the border, she would call out, "Glory to God and Jesus, too. One more soul is safe!"

Harriet Tubman even carried a revolver as protection from slave catchers and their dogs. She also threatened to shoot anyone who tried to turn back since that would risk the safety of the remaining group, as well as anyone who helped them on the way. Harriet Tubman spoke of one man who insisted he was going to go back to the plantation. She pointed the gun at his head and said, "Go on or die.” Several days later, the man who wavered crossed into Canada with the rest of the group.

By the late 1850s, Eastern Shore slaveholders were holding public meetings about the large number of escapes in the area; they cast suspicion on free blacks and white abolitionists. They did not know that "Minty", the petite, disabled woman who had run away years before, was responsible for freeing so many enslaved people. An abolitionist named Sallie Holley wrote that $40,000 "was not too great a reward for Maryland slaveholders to offer for her”. I checked some calculators, and 40,000 would be worth over one million dollars today.

Fortunately Tubman and the fugitives she assisted were never captured. Years later, she told an audience: "I was conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can't say – I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger."

In early 1859, Frances Adeline Seward, the wife of abolitionist Republican U.S. Senator William H. Seward, sold Tubman a seven-acre farm in Fleming, New York,[or $1,200 (equivalent to over 50,000 today., The adjacent city of Auburn was a hotbed of antislavery activism, and Tubman took the opportunity to move her parents from Canada back to the U.S. Her farmstead became a haven for Tubman's family and friends. For years, she took in relatives and boarders, offering a safe place for black Americans seeking a better life in the north.

In November 1860, Tubman conducted her last rescue mission. Throughout the 1850s, Tubman had been unable to effect the escape of her sister Rachel, and Rachel's two children Ben and Angerine. Upon returning to Dorchester County, Tubman discovered that her sister Rachel had died, and the children could be rescued only if she could pay a bribe of $30 (equivalent to over 1000 dollars today.) She did not have the money, so the children remained enslaved. Their fates remain unknown.

In the run-up to the American Civil War and the discussion of whether to free the slaves, one proposal that gained some traction was repatriation or colonization–that is, sending black Americans, enslaved and free people alike, back to Africa. And in 1859, Harriet Tubman used a speech to share her own views on the issue. It happened at a meeting of the New England Colored Citizens’ Convention, where the audience had voted to condemn the proposed repatriation.

As the Boston abolitionist paper The Liberator reported, Tubman used a simple fable to counter the argument for sending black Americans back to Africa. She told the story of a:

man who sowed onions and garlic on his land to increase his dairy productions; but he soon found the butter was strong and would not sell, and so he concluded to sow clover instead. But he soon found the wind had blown the onions and garlic all over his field. Just so, she said, the white people had got the slave here to do their drudgery, and now they were trying to root the slaves out and send ’em to Africa. “But,” she said, “they can’t do it; we’re rooted here, and they can’t pull us up.”

In summary, Tubman’s story got its point across.

In Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero, historian Kate Clifford Larson notes that Tubman was exceptionally smart politically, and important as a storyteller - representing black women at a time when they were rare on the speaking stage: Larson writes about Tubman -

A great storyteller she was…She moved her audiences deeply. Plainly dressed, very short and petite, quite black-skinned, and missing front teeth, Tubman physically made a stark contrast to Sojourner Truth, one of the most famous former slave women then speaking on the antislavery lecture circuit, who was nearly six feet tall….Like Truth, however, Tubman shocked her audiences with stories of slavery and the injustices of life as a black woman. Black men dominated the antislavery lecture circuit. Tubman and Truth stood for millions of slave women whose lives were marred by emotional and physical abuse at the hands of white men.

Larson’s biography of Tubman shares many insights about her public speaking–a skill of Tubman’s we have largely forgotten in simplifying her memory and story. To be a woman of color who spoke in public in her time was rare, and challenge after challenge faced her as a speaker. Like Sojourner Truth, she was accused of being a man in part due to her speaking skills. In speeches like this one, she often was not introduced by her real or full name, to build up the mystery and excitement, but also taking away her identity in public, sometimes in the name of protecting her safety. Her words were often rewritten for her by biographers and reporters. Because Tubman herself could not read or write, her spoken word was both powerful and ephemeral. Speaking was essential in her career, a way for Tubman to raise funds and earn an income to support her work and her family.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Tubman had a vision that the war would soon lead to the abolition of slavery. More immediately, enslaved people near Union positions began escaping in large numbers. General Benjamin Butler declared these escapees to be "contraband" – property seized by northern forces – and put them to work, initially without pay, at Fort Monroe in Virginia. The number of "contrabands" encamped at Fort Monroe and other Union positions rapidly increased.In January 1862, Tubman volunteered to support the Union cause and began helping refugees in the camps, particularly in Port Royal, South Carolina.

In South Carolina, Tubman met General David Hunter, a strong supporter of abolition. He declared all of the "contrabands" in the Port Royal district free, and began gathering formerly enslaved people for a regiment of black soldiers. At this time, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln was not yet prepared to enforce emancipation on the southern states and reprimanded Hunter for his actions. Tubman condemned Lincoln's response and his general unwillingness to consider ending slavery in the U.S., for both moral and practical reasons: She was quoted as saying -

God won't let master Lincoln beat the South till he does the right thing. Master Lincoln, he's a great man, and I am a poor negro; but the negro can tell master Lincoln how to save the money and the young men. He can do it by setting the negro free.

Later that year, Tubman's intelligence gathering played a key role in the raid at Combahee Ferry. She guided three steamboats with black soldiers under Montgomery's command past mines on the Combahee River to assault several plantations. Once ashore, the Union troops set fire to the plantations, destroying infrastructure and seizing thousands of dollars worth of food and supplies. Forewarned of the raid by Tubman's spy network, enslaved people throughout the area heard steamboats' whistles and understood that they were being liberated. Tubman watched as those fleeing slavery stampeded toward the boats; she later described a scene of chaos with women carrying still-steaming pots of rice, pigs squealing in bags slung over shoulders, and babies hanging around their parents' necks. Armed overseers tried to stop the mass escape, but their efforts were nearly useless in the tumult. As Confederate troops raced to the scene, the steamboats took off toward Beaufort with more than 750 formerly enslaved people.

Newspapers heralded Tubman's "patriotism, sagacity, energy, [and] ability" in the raid, and she was praised for her recruiting efforts – more than 100 of the newly liberated men joined the Union army. Her role in the raid led to her being widely credited as the first woman to lead U.S. troops in an armed assault.

In July 1863, Tubman worked with Colonel Robert Gould Shaw at the assault on Fort Wagner, reportedly serving him his last meal. By the way, you may remember Colonel Shaw as the main character, played by Matthew Broderick, in the movie Glory

Harriett Tubman later described the battle to historian Albert Bushnell Hart:

And then we saw the lightning, and that was the guns; and then we heard the thunder, and that was the big guns; and then we heard the rain falling, and that was the drops of blood falling; and when we came to get the crops, it was dead men that we reaped.

Join Celebrate Poe for the final podcast episode of a three part series regarding Harriett Tubman - a podcast episode that will be released as soon as this drops. This third episode, called Dangerous Missions,

Deals with her place in history, as well as a comparison of Tubman with Frederick Douglas and Edgar Allan Poe.

Sources include: Harriet: The Moses of Her People by Sarah H. Bradford,

Thank you for listening to Celebrate Poe.